In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche posits that art, particularly tragic art, has the ability to cure the nausea one experiences after re-entering everyday reality after engulfed in the Dionysian state.

It is a balm that soothes the turmoil within our beings after seeing the true nature of living, the death and destruction inherent in the history of the world.

Requiem for a Dream (2000) is an example of a tragic performance meant to evoke an affirmative life lesson, but when I watched it, it could be argued that the ending instead signals relentless despair and a failure to accept the true nature of life--one that leaves viewers with less of a cheerful passivity but a sobering, stasis of apollonian delusion.

Nietzsche states in The Birth of Tragedy (BT), that the Greeks knew how to affirm life for all of its beauty and destruction through the doctrine of tragedy. The essential knowledge that all humans will die and become a part of the nothingness of the universe is what becomes uncovered in the Greek tragic plays. The duality of the Apollonian and Dionysian become clearer and clearer throughout each section of BT and we are able to articulate the oppositional nature as such: for the ‘Delphic god’, Apollo is the god of truth and is associated with sculpture, divination, dreams, contemplation, and illusion.

The establishing scene of the film shows a standoff between Sara and her son, Henry, who pawns her television set in order to purchase some narcotics. This is later revealed to be a routine occurrence when in a follow-up scene Sara explains her reasonings to the pawn shop owner on why she continuously relents to her son’s addiction as opposed to seeking help for him. Thus we are introduced to Sara Goldfarb, our elderly main character in Requiem, a widow with a son addicted to heroin who spends most of her twilight years in front of the television.

It is this routine, mundane moment- a commercial for a juice-based diet looping endlessly-when she gets her dream call that she is a winner to be a contestant on a tv show. Her fixation thus turns from watching television to being on television. This obsession particularly manifests in a desire to lose weight in order to gain a sense of self confidence back and as it is later shown, to harken back to a time where things were still alright in her family as exemplified in the motif of the red dress she wears in a photo of Henry’s high school graduation.

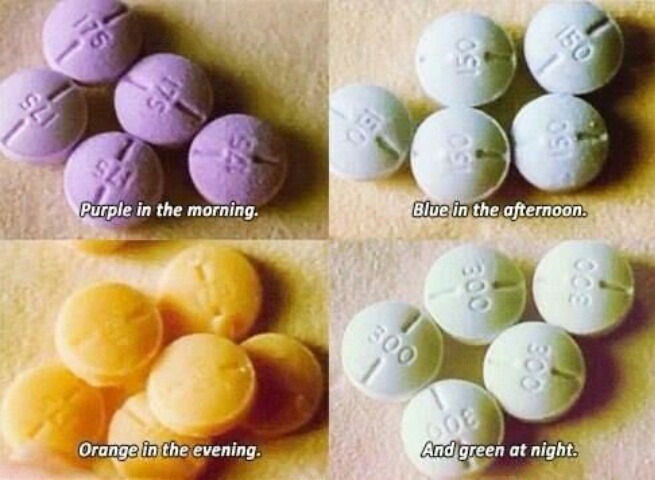

In the photo, her husband was still alive, her son Henry had an infinite amount of possibility when it came to life, and she still fit a certain red dress. This red dress becomes the main focus of her life and she unfortunately becomes addicted to amphetamines prescribed by a dietician in order to help her lose weight. What she ends up losing is her sanity.

Each of the character’s drug use is an attempt to fulfill their desires but fall short of this and end up as simply delusions. Sara in particular breaks down in one scene to Henry who is questioning her apparent drug use, and frankly states that she has nothing left to live for. Why is it so wrong that she loses herself in her television, when Henry isn’t around, her husband has died, and the crux of it all- she is old, and therefore facing the capital T, TRUTH, of nature. Her youth is gone, the winter of her discontent is nigh and she is coping. Not through an Oedipal passivity, or a Promethean activity, but an apollonian illusion that if she appeared on television just once, people will love her and her life will have true meaning.

We can interpret the character of Sara Goldfarb as the drunken reveler described by Nietzsche in TBoT, who upon sinking into dionysian revelry, mistakes the hallucinations therein as messages from the gods and remains in stasis. Replace the ‘Gods’ with the prominence of television and the banality of modernity and Sara fits right into place with masses of other individuals searching for their meaning in a ‘veil of forgetfulness’ that they have forgotten are illusions.

We see this nullification of the will through the habitual intake of hard drugs for the main characters sublimated into what we describe earlier as a pathologic necessity. The obliteration of the will when re-entering consciousness after the euphoric effects of the drugs creates a dependency that makes everyday reality a nauseating experience that-towards the end of the film- cannot be assuaged with art or a fervent affirmation of life through art. Addiction is the apollonian logic taken to its conclusion. But the tragic affirmation of life isn’t in the cliched arguments many viewers may come away with after watching the film. It is the reality that underneath the anti-drug abuse warnings proliferated throughout the film there is a deep human yearning to escape our inevitable truth and the despair that accompanies that inevitability.

No comments:

Post a Comment